Czym jest przezskórna interwencja wieńcowa (PCI)?

Przezskórna interwencja wieńcowa (PCI) to zabieg umożliwiający ponowne otwarcie lub rozszerzenie zamkniętych bądź zwężonych naczyń wieńcowych serca za pomocą cewnika.

Celem jest możliwie szybkie przywrócenie ukrwienia mięśnia sercowego, co pomoże uniknąć jego obumarcia. Często używa się synonimu przezskórna angioplastyka wieńcowa (percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty – PTCA).

Historia

- Do późnych lat 70. XX w. przywrócenie ukrwienia mięśnia sercowego było możliwe tylko za pomocą pomostowania aortalno-wieńcowego, tak zwanych bypassów.

- Przezskórna interwencja wieńcowa zaczęła zyskiwać na popularności od czasu przeprowadzenia pierwszej angioplastyki balonowej (rozszerzenie naczyń krwionośnych za pomocą cewnika balonowego) w 1977 r.

- Pierwsze stenty wszczepiono pacjentom pod koniec lat 80. XX wieku.

- Stenty uwalniające leki (DES = Drug Eluting Stents) wprowadzono z kolei w 2002 r.

W jaki sposób przeprowadza się przezskórną interwencję wieńcową?

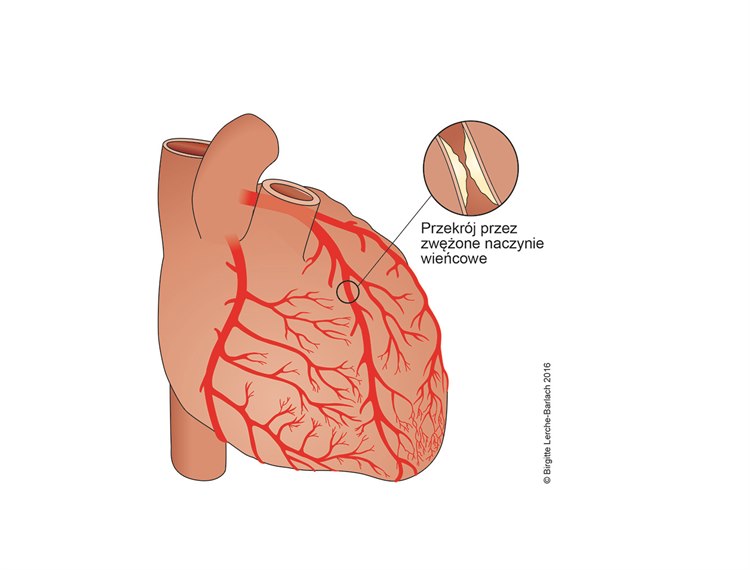

Cewnikowanie serca wykonuje się w tzw. pracowni hemodynamicznej. Pacjent leży na specjalnym stole zabiegowym, a lekarz dokładnie bada wydolność układu krwionośnego. Po znieczuleniu wybranego miejsca przedramienia lub pachwiny zastrzykiem naczynie krwionośne nakłuwa się przez skórę igłą. Pod kontrolą RTG przesuwa się następnie w kierunku serca cienki wężyk zwany cewnikiem. Umożliwia to wprowadzenie środka kontrastującego, dzięki któremu widoczne są naczynia wieńcowe serca. Na podstawie rozprzestrzenienia środka kontrastującego wykrywa się zwężenie naczyń wieńcowych serca. Dzięki temu lekarze wiedzą, które naczynia krwionośne są objęte zmianami chorobowymi i należy je ponownie otworzyć lub rozszerzyć. Można to zrobić za pomocą balona. W tym celu cewnik wprowadza się do miejsca zwężenia i napełnia płynem, tak aby balon rozszerzył się na końcu cewnika, poszerzając naczynie od wewnątrz. Zazwyczaj podczas tego samego zabiegu wprowadza się stent (patrz ilustracja). W przypadku niektórych pacjentów konieczne jest zastosowanie kilku stentów. Dotyczy to osób, u których zamknięcie naczynia krwionośnego nastąpiło na dłuższym odcinku. Dostępne są różne typy stentów. Zazwyczaj są wykonane z powlekanej metalowej kratki, która w pierwszych tygodniach po implantacji uwalnia także leki hamujące przyrastanie do ściany naczynia. Z uwagi na to, że na stencie może dojść do ponownego powstania zakrzepu, po zabiegu pacjenci powinni przez pewien czas przyjmować leki rozrzedzające krew.

Kiedy przeprowadza się przezskórną interwencję wieńcową?

PCI przeprowadza się u pacjentów cierpiących na ostry zespół wieńcowy, czyli ból w klatce piersiowej wywołany przez zawał serca lub niestabilną dusznicę bolesną. Zabieg przeprowadza się obecnie w wielu szpitalach.

- W przypadku zwężenia tętnic wieńcowych może się zdarzyć, że niektóre obszary serca nie będą odpowiednio zaopatrywane w krew, zwłaszcza w przypadku wysiłku fizycznego lub znacznego zdenerwowania. Uwidacznia się to u pacjentów w postaci silnego bólu lub uczucia ucisku w klatce piersiowej. Takie objawy noszą miano dusznicy bolesnej.

- Zawał serca jest spowodowany zablokowaniem naczynia wieńcowego serca przez skrzep krwi. Chorobę podstawową stanowi często choroba wieńcowa serca. W niektórych przypadkach u pacjentów występowały już kiedyś napady dusznicy bolesnej. Występuje zmniejszenie przepływu krwi do tkanki mięśniowej zaopatrywanej przez zablokowane naczynie krwionośne. Brak odpowiednio szybkiego przywrócenia zaopatrzenia tkanki spowoduje obumarcie określonych komórek serca.

W przypadkach innych niz ostre zespoły wieńcowe decyzja dotycząca przeprowadzenia PCI jest nieco trudniejsza. Dotychczas nie wykazano przewagi PCI nad farmakoterapią.

W przypadku zwężenia kilku naczyń wieńcowych serca operacja wszczepienia bypassów zapewnia nieco lepsze rezultaty niż implantacja stentów. Operacja wszczepienia bypassów pozwala zmniejszyć ryzyko ponownego zamknięcia naczyń krwionośnych, lecz potęguje jednocześnie ryzyko udaru. Decyzję dotyczącą najlepszej metody leczenia należy podejmować, uwzględniając sytuację poszczególnych pacjentów.

Dodatkowe informacje

Deximed

- Dusznica bolesna

- Zawał serca

- Ostry zespół wieńcowy

- Przezskórna interwencja wieńcowa – informacje dla lekarzy

Ilustracje

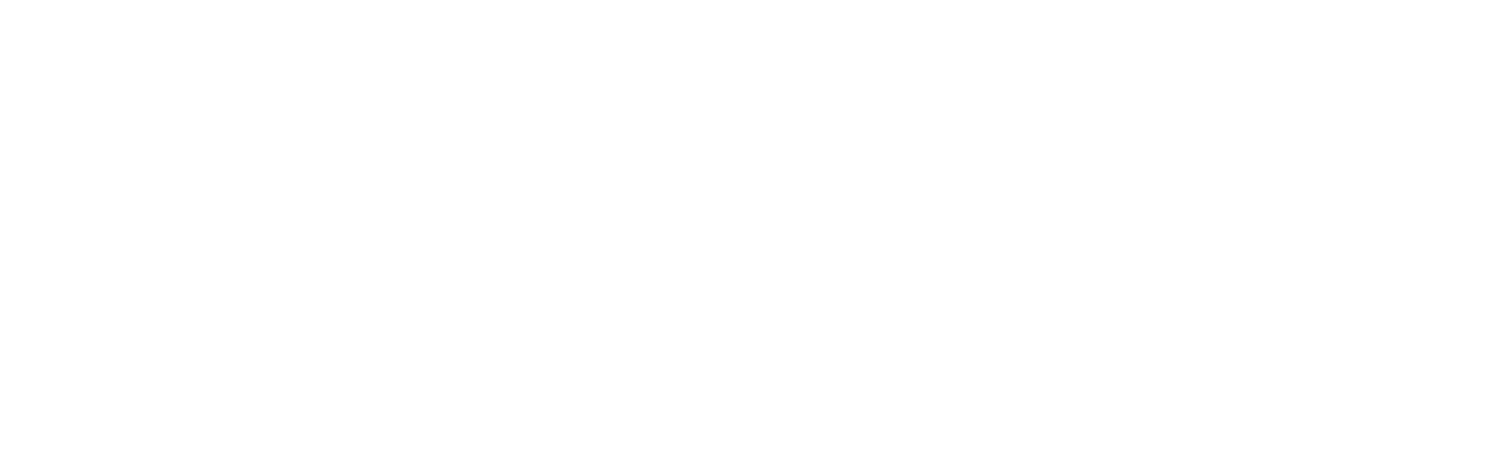

Tętnica wieńcowa serca, zwężenie

Tętnica wieńcowa serca, zwężenie Udrażnianie zwężonego naczynia krwionośnego stentami

Udrażnianie zwężonego naczynia krwionośnego stentamiAutorzy

- Prof. Sławomir Chlabicz, redaktor/recenzent

- Dr n. med. Hannah Brand, lekarka, Berlin

Link lists

Authors

Previous authors

Updates

Gallery

Snomed

References

Based on professional document Przezskórna interwencja wieńcowa. References are shown below.

- Diodato M, Chedrawy E. Coronary Artery Bypass Graft Surgery: The Past, Present, and Future of Myocardial Revascularisation. Surgery Research and Practice 2014; 2014: 1-6. doi:10.1155/2014/726158 DOI

- Gruentzig A. Results from coronary angioplasty and implications for the future. Am Heart J 1982; 103: 779-783. doi:10.1016/0002-8703(82)90486-0 DOI

- Sigwart U, Puel J, Mirkovitch V, et al. Intravascular stents to prevent occlusion and restenosis after transluminal angioplasty. New Engl J Med 1987; 316: 701-716. pmid:2950322 PubMed

- Serruys P, de Jaegere P, Kiemeneij F, et al. A comparison of balloon-expandable-stent implantation with balloon angioplasty in patients with coronary artery disease.. New Engl J Med 1994; 331: 489-495. doi:10.1056/NEJM199408253310801 DOI

- Dehmer GJ, Smith KJ. Drug-eluting coronary artery stents. Am Fam Physician 2009; 80: 1245-51. pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

- Nikam N, Steinberg T, Steinberg D. Advances in stent technologies and their effect on clinical ef cacy and safety. Med Devices (Auckl) 2014; 2014: 165-178. doi:10.2147/MDER.S31869 DOI

- Parisi A, Folland E, Hartigan P, et al. A comparison of angioplasty with medical therapy in the treatment of single-vessel coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med 1992; 326: 10-16. doi:10.1056/NEJM199201023260102 DOI

- Yang EH, Gumina RJ, Lennon RJ, Holmes DR Jr, Rihal CS, Singh M. Emergency coronary artery bypass surgery for percutaneous coronary interventions: changes in the incidence, clinical characteristics, and indications from 1979 to 2003. J Am Coll Cardiol 2005; 46: 2004-9. PubMed

- McBride W, Lange RA, Hillis LD. Restenosis after successful coronary angioplasty. Pathophysiology and prevention. N Engl J Med 1988; 318: 1734-7. New England Journal of Medicine

- Serruys P, Luijten H, Beatt K, et al. Incidence of restenosis after successful coronary angioplasty: a time-related phenomenon. A quantitative angiographic study in 342 consecutive patients at 1, 2, 3, and 4 months. Circulation 1988; 77: 361-371. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.77.2.361 DOI

- Gershlick A, de Bono D. Restenosis after angioplasty. Br Heart J 1990; 64: 351-353. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

- Fischman DL, Leon MB, Baim DS, et al., Stent Restenosis Study Investigators. A randomized comparison of coronary-stent placement and balloon angioplasty in the treatment of coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med 1994; 331: 496-501. New England Journal of Medicine

- Mintz GS, Hoffmann R, Mehran R, et al. In-stent restenosis: the Washington Hospital Center experience. Am J Cardiol 1998; 81: 7E–13E. www.ajconline.org

- Ho M, Chen C, Wang C, et al. The Development of Coronary Artery Stents: From Bare-Metal to Bio-Resorbable Types. Metals 2016; 6: 168. doi:10.3390/met6070168 DOI

- Moses JW, Leon MB, Popma JJ, et al., for the SIRIUS Investigators. Sirolimus-eluting stents versus standard stents in patients with stenosis in a native coronary artery. N Engl J Med 2003; 349: 1315-23. New England Journal of Medicine

- Roiron C, Sanchez P, Bouzamondo A, Lechat P, Montalescot G. Drug eluting stents: an updated meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Heart 2006; 92: 641-9. PubMed

- Byrne R, Joner M, Kastrati A. Stent thrombosis and restenosis: what have we learned and where are we going? The Andreas Grüntzig Lecture ESC 2014. Eur Heart J 2015; 36: 3320–3331. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehv511 DOI

- Byrne RA, Rossello X, Coughlan JJ, et al. 2023 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J. 2023 Oct 12;44(38):3720-3826. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehad191. Erratum in: Eur Heart J. 2024 Apr 1;45(13):1145. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehad870. PMID: 37622654. www.escardio.org

- Bønaa K, Mannsverk J, Wiseth R, et al. Drug-Eluting or Bare-Metal Stents for Coronary Artery Disease. New Engl J Med 2016; 375: 1242-1252. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1607991 DOI

- Sarno G, Bo Lagerqvist1 B, Fröbert O, et al. Lower risk of stent thrombosis and restenosis with unrestricted use of ‘new-generation’ drug-eluting stents: a report from the nationwide Swedish Coronary Angiography and Angioplasty Registry (SCAAR). Eur Heart J 2012; 33: 606–613. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehr479 DOI

- Iqbal J, Gunn J, Serruys P. Coronary stents: historical development, current status and future directions. Br Med Bull 2013; 106: 193–211. doi:10.1093/bmb/ldt009 DOI

- Kristensen S, Knuuti J, Saraste A, et al. 2014 ESC/ESA Guidelines on non-cardiac surgery: cardiovascular assessment and management. Eur Heart J 2014; 35: 2383-2431. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehu282 DOI

- Valgimigli M, Bueno H, Byrne R, et al. 2017 ESC focused update on dual antiplatelet therapy in coronary artery disease developed in collaboration with EACTS. Eur Heart J 2018; 39: 213–254. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehx419 DOI

- Iqbal J, Onuma Y, Ormiston J, et al. Bioresorbable scaffolds: rationale, current status, challenges, and future. Eur Heart J 2014; 35: 765-776. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/eht542 DOI

- Ali Z, Serruys P, Kimura T, et al. 2-year outcomes with the Absorb bioresorbable scaffold for treatment of coronary artery disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of seven randomised trials with an individual patient data substudy. Lancet 2017; 390: 760-772. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31470-8 DOI

- Scheller B, Hennen B, Severin-Kneib S, et al. Long-term follow-up of a randomized study of primary stenting versus angioplasty in acute myocardial infarction. Am J Med 2001; 110: 1-6. pmid:11152857 PubMed

- Nordmann A, Hengstler P, Harr T, et al. Clinical Outcomes of Primary Stenting versus Balloon Angioplasty in Patients with Myocardial Infarction: A Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Am J Med 2004; 116: 253-262. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2003.08.035 DOI

- Kastrati A, Dibra A, Spaulding C, et al. Meta-analysis of randomized trials on drug-eluting stents vs. bare-metal stents in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J 2007; 28: 2706-2713. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehm402 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

- Räber L, Kelbak H, Ostojic M, et al. Effect of biolimus-eluting stents with biodegradable polymer vs bare-metal stents on cardiovascular events among patients with acute myocardial infarction: the COMFORTABLE AMI randomized trial. JAMA 2012; 308: 777-787. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.10065 DOI

- Sabate M, Cequier A, Iniguez A, et al. Everolimus-eluting stent versus bare-metal stent in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (EXAMINATION): 1 year results of a randomised controlled tria. Lancet 2012; 380: 1482–1490. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61223-9 DOI

- Sabate M, Brugaletta S, Cequier A, et al. Clinical outcomes in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction treated with everolimus-eluting stents versus bare-metal stents (EXAMINATION): 5-year results of a randomised trial. Lancet 2016; 357: 357-366. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00548-6 DOI

- Collet J, Thiele H, Barbato E, et al. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation. Eur Heart J 2020; 00: 1-79. www.escardio.org

- Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, et al. 2017 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation. leitlinien.dgk.org

- Boden W, O'Rourke R, Teo K, et al. Optimal Medical Therapy with or without PCI for Stable Coronary Disease. New Engl J Med 2007; 356: 2007. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa070829 DOI

- The BARI 2D Study Group. A Randomized Trial of Therapies for Type 2 Diabetes and Coronary Artery Disease. New Engl J Med 2009; 360: 2503-2515. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0805796 DOI

- Nishigaki K, Yamazaki T, Kitabatake A, et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention plus medical therapy reduces the incidence of acute coronary syndrome more effectively than initial medical therapy only among patients with low-risk coronary artery disease a randomized, comparative, multicenter study. J Am Coll Cardiol Intv 2008; 1: 469-479. doi:10.1016/j.jcin.2008.08.002 DOI

- Stergiopoulos K, Brown D. Initial Coronary Stent Implantation With Medical Therapy vs Medical Therapy Alone for Stable Coronary Artery Disease. Arch Intern Med 2012; 172: 312-319. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2011.1484 DOI

- Park S, Ahn J, Kim Y, et al. Trial of Everolimus-Eluting Stents or Bypass Surgery for Coronary Disease. New Engl J Med 2015; 372: 1204-1212. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1415447 DOI

- Bangalore S, Guo Y, Samadashvili Z, et al. Everolimus-Eluting Stents or Bypass Surgery for Multivessel Coronary Disease. New Engl J Med 2015; 372: 1213-1222. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

- Mohr F, Morice M, Kappetein K, et al. Coronary artery bypass graft surgery versus percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with three-vessel disease and left main coronary disease: 5-year follow-up of the randomised, clinical SYNTAX trial. Lancet 2013; 381: 629–638. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60141-5 DOI

- Jaffe R, Strauss B. Late and Very Late Thrombosis of Drug-Eluting Stents. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007; 50: 119-127. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2007.04.031 DOI

- Lüscher TF, Steffel J, Eberli FR, et al. Drug-eluting stent and coronary thrombosis: biological mechanisms and clinical implications. Circulation 2007; 115: 1051-8. PubMed

- Sudhir K, Hermiller J, Ferguson J, et al. Risk Factors for Coronary Drug-Eluting Stent Thrombosis: Influence of Procedural, Patient, Lesion, and Stent Related Factors and Dual Antiplatelet Therapy. ISRN Cardiology 2013; 2013: 1-8. doi:10.1155/2013/748736 DOI

- Iakovou I, Schmidt T, Bonizzoni E, et al. Incidence, predictors, and outcome of thrombosis after successful implantation of drug-eluting stents. JAMA 2005; 293: 2126-30. pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

- Spertus JA, Kettelkamp R, Vance C, et al. Prevalence, predictors, and outcomes of premature discontinuation of thienopyridine therapy after drug-eluting stent placement: results from the PREMIER registry. Circulation 2006; 113: 2803-9. pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

- Kotani J, Awata M, Nanto S, et al. Incomplete neointimal coverage of sirolimus-eluting stents: angioscopic findings. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006; 47: 2108-2111. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2005.11.092 DOI

- Pfisterer M, Brunner-La Rocca H, Buser P, et al. Late clinical events after clopidogrel discontinuation may limit the benefit of drug-eluting stents: an observational study of drug-eluting versus bare-metal stents. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007; 48: 2584-2591. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2006.10.026 DOI

- Malenka DJ, Kaplan AV, Lucas FL, Sharp SM, Skinner JS. Outcomes following coronary stenting in the era of bare-metal vs the era of drug-eluting stents. JAMA 2008; 299: 2868-76. PubMed

- Mauri L, Hsieh WH, Massaro JM, Ho KK, D'Agostino R, Cutlip DE. Stent thrombosis in randomized clinical trials of drug-eluting stents. N Engl J Med 2007; 356: 1020-9. New England Journal of Medicine

- Montalescot G, Sechtem U, Achenbach S, et al. 2013 ESC guidelines on the management of stable coronary artery disease. Eur Heart J 2013; 34: 2949-3003. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

- Stefanini G, Kalesan B, Serruys P, et al. Long-term clinical outcomes of biodegradable polymer biolimus-eluting stents versus durable polymer sirolimus-eluting stents in patients with coronary artery disease (LEADERS): 4 year follow-up of a randomised non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2011; 378: 1940–1948. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61672-3 DOI

- European Society of Cardiology and European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery. Guidelines on myocardial revascularization, Stand 2018. www.escardio.org

- Knuuti J, Wijns W, Saraste A, et al. 2019 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of chronic coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J 2020; 41: 407-477. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehz425 www.escardio.org

- Eikelboom J, Connolly S, Bosch J, et al. Rivaroxaban with or without Aspirin in Stable Cardiovascular Disease. N Engl J Med 2017; 377: 1319-1330. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1709118 DOI

- Schüpke S, Neumann F, Menichelli M, et al. Ticagrelor or Prasugrel in Patients With Acute Coronary Syndromes. N Engl J Med 2019; 381: 1524-1534. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1908973 DOI

- Hindricks G, Potpara T, Dagres N, et al. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur Heart J 2020; 00: 1-126. www.escardio.org

- Trenk D. Proton pump inhibitors for prevention of bleeding episodes in cardiac patients with dual antiplatelet therapy - between Scylla and Charybdis? Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther 2009;47(1):1-10. pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

- Eisenberg MJ, Richard PR, Libersan D, Filion KB. Safety of short-term discontinuation of antiplatelet therapy in patients with drug-eluting stents. Circulation 2009; 119: 1634-42. pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov